[1] (…) He laid his hand upon the limbs; the ivory felt soft to his touch and yielded to his fingers like the wax of Hymnettus. It seemed to be warm. He stood up; his mind oscillated between doubt and joy. Fearing he may be mistaken, again and again with a lover’s ardor he touches the object of his hopes. I was indeed alive! The veins when pressed yielded to the finger and again resumed their roundness. Slowly it dawned on Pygmalion that the animation of his sculpture was the result of his prayer to Goddess Aphrodite who knew his desire. At last, the votary of Aphrodite found words to thank the goddess. Pygmalion humbled himself at the Goddess’ feet. Ovid, Metamorphoses A just note, on time… Let us begin by making a reference to film reviews. How should we as analysts evaluate comments and reviews made on films? Cinema specialists seem to agree that ‘The Skin I Live In’ is Almodóvar’s most imperfect film. Some have treated certain scenes brutally, judging them excessive, badly filmed, expendable, etc. And they are probably right -just as right as we are when we say that it is a great film, possibly the best in the Spanish director’s long career. How is this possible? Can film critics and we, the analysts, both be right despite such discrepancy? In his well known essay on cinema and philosophy, Alain Badiou underlines the fundamental differences between the cinema and the rest of the arts. While the latter seeks to find purity in the creative act –such as painting and writing that build the perfection of their work from a clean sheet of paper or canvass – the cinema operates in exactly the opposite way. At the start of a film there are too many things to contend with – infinite amounts of scripts, many actors, multiple scenographies … and the task of the artist lies in discarding, eliminating part of the material and giving shape to his work with what is left, with what emerges from that process. This is why Badiou compares cinematographic creation with waste management. This is also the reason why in any film, even in those we consider works of art, there are unnecessary elements – deplorable secondary actors, sentimental music, unnecessary pornography, etc. In conclusion, it is the spectator in the theatre hall who during the exhibition of the film, finishes the construction of the work as he handles some of that transformation, of that depuration. As Alain Badiou constantly reminds us, “the relationship with the cinema is not a relationship of contemplation. (….) In the cinema we have the body to body, we have the battle, we have the impure and therefore, we are not in the contemplation. We are of necessity, in the participation, we participate in this combat, we judge the victories, we judge the defeats and we take part in the creation of some moments of purity.” (Badiou, 2004, page 71) If it is the spectator who wages that battle in which the creative act participates, a good film will then be that in which there are many defeats, but some great victories. And there lies the difference between the critic and the analyst. Where the former sees a badly filmed scene, the latter can read the magic of a significant; the significant that retroactively allows you to build an unexpected twist that reconciles us with the film, but not in the manner of a rational, conscious operation, but as an effect that is felt in the body of the spectator. When we go to the cinema we are not looking for purity, and for that reason we can find it and be surprised by it, there where error is revealed to us as virtue, and the false step like an unexpected, calculated hesitation of a filmmaker. There is an expression in music that says: “one false note spoils a fugue, but one just note, on time, saves a symphony.” The Skin I Live In’ was not conceived as a fugue but more as a symphony. The fugue, let us remember, is the musical form made immortal by Bach characterized by a perfect conception of thematic counterpoints, organized according to a logical mathematical system – which is why just one false note is needed to spoil the whole musical rendition. In the fugue we are stricken by necessity. The symphony on the other hand, can have difficult, unhappy moments, but it is always capable of rescuing itself if there is a victory – a masterly oboe, a sole, clear and inspired clarinet. Chance can find its way into a symphony, only if the artist and the spectator do something with it. [2] The Skin I Live In is a film that constructs itself as it unfolds. a film that might sometimes encounter defeats but the film ends in a victory of such extraordinary proportions that it is liberated from failure and becomes a work of art. De humani corpori fabrica A second key to access Almodóvar’s film is to consider one of the posters with which his film was promoted. The image recreates illustrations by Andrea Vesalio, a Flemish doctor who revolutionized medicine by publishing, in 1543, his famous treaty on anatomy entitled De humani corpori fabrica. The work was conceived during the transition from feudalism to modern capitalism, in the middle of the process of land’s losing its hegemonic economic role and its replacement by machinery, with the consequent fall of metaphysical thought and the growing prominence of reason.Up until the publication of Vesalio’s work, surgery was governed by the precepts of Galen, a Greek physician who in the 2nd century AD formalized the anatomy of the human body based on his studies on pigs and monkeys – dissection of human corpses was forbidden for religious reasons. Vesalio was the first to dare defy Galen’s knowledge and performed dissections before crowded auditoriums in the University of Padua’s School of Medicine, pointing out some of the mistakes that had persisted for centuries. The coexistence in Vesalio of this growing rationality with monarchical, medieval roots can be seen in the introduction of his De humani corpore fabrica, where the following dedication is found: “Preface of Andreas Vesalius to his own books on the anatomy of the human body addressed to The Most Great and Invincible emperor The Divine Charles V” [3] What does this reference to the fabrica of the human body in the poster of the film say to us? It says that it is possible to read the work of Almodóvar as a testimony of a new step forward in scientific rationality. A perfectly feasible story in which transformations of the body reach a degree of extreme sophistication. Rhinoplasty, face transplants, breast hypoplacia, vaginoplasty and xenotransplantation, are some of the techniques used by Dr. Robert Ledgardt, the plastic surgeon played by Antonio Banderas. What are the ethical limits in cosmetic and restorative surgery? When the progress Vesalio dreamed of reaches the extreme described in the film, it becomes necessary to adopt a criterion that goes beyond moral positions. In order to do this it will be necessary to establish when a scientific-technological breakthrough represents a valuable instrumental mediation destined to restore a function, and when instead, it risks situating the subject in an irreversible deficit. This difference, expressed by Armando Kletnicki in terms of symbolic transformation and affectation of a true nucleus (Kletnicki, 2000), is an ethical device in the sense that it does not offer an automatic reply to the problem -what it does is to open the path to discussion on the singularity of the case, thus generating new and disturbing questions. On this same line, the latent references to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio and in particular, the myth of Pygmalion, can be read in Almodovar’s film. A few words on Pygmalion. In his Metamorphoses Ovid introduces the story of Pygmalion, the King of Cyprus who sought to marry the perfect woman. Frustrated in his futile search, he dedicates his life to sculpting, imagining his ideal beloved in ivory and marble. He finally falls in love with one of his creations, Galatea, to whom Aphrodite concedes life, thus making Pygmalion’s dream come true – Ovid’s beautiful passage can be read in the epigraph of this article. The series is not fortuitous. A sculptor that falls hopelessly in love with his creation, a carpenter who makes a puppet that will turn into a child, a doctor that gives life to his creature by means of pseudoscientific artifices. Once again, what is the limit between creative fiction and the falsification of creative knowledge? [4] Transmission of a deadly heritage As in other films by Almodóvar, critics debate whether to consider The Skin I Live In a comedy or a melodrama. For us, it is decidedly a tragedy, in the ancient meaning of the word, such as manifested by Aristotle in his Poetics: “A tragedy, then, is a mimesis of an action that is elevated, complete and of magnitude, complete in itself; in language with pleasurable accessories, each kind brought in separately in the parts of the work; in a dramatic, not in a narrative form; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catarsis of such emotions.” (Imgram Bywater: 35) [5] Eteocles and Polynices, the sons of Oedipus, pay with their mutual deaths - each in the hands of the other - for the arrogance of having wanted to rule despite knowing themselves to be the sons of crime and incest. In The Skin I Live in the audacity of the brothers will also be punished – they will pay the price of their ignorance whenever they are the fruit of the same womb who nevertheless disowns them. Once again, the impossibility of a desire that is not anonymous – in this case in the form of fraudulent adulteration of identity - returns as ravage in the following generation. To continue with this tragic thread in Almodóvar, it is essential to make reference to Laius, the first on record pedophile inherited from western mythology. Let us briefly recapitulate the story. The king of Pisa entrusts Laius with the care and education of his son Chrysippus. Laius falls in love with the child, kidnaps and sexually abuses him. Chrysippus is said to have killed himself out of anguish and shame and the crime committed by Laius was left unpunished. Apollo, God and Protector of young men, condemns Laius and his future son: “No son are you to have, for if you do, that boy will kill his own father and sleep with his own mother.” This is how, when Oedipus is born, Laius sends somebody to have him killed to prevent the design of the Gods from happening. As it is known, the executioner takes pity on the baby and hands it to King and Queen of Corinth who bring him up as their own child. When Oedipus grows into adulthood and consults the oracle, he receives the message “You shall kill thy father and sleep with thy mother”. He desperately flees from Corinth seeking to escape his fate only to meet it. In short, Laius’ pedophilia is passed on, as a curse, to his son Oedipus, who in turn will bestow this tragedy to his own descendants; the ravage that later reaches his sons Eteocles and Polyneces, as well as Antigone. Pedophilia in the first generation becomes crime and incest in the second and massacre and insult to bodies in the third. [6] References found in The Skin I Live In will be the result of the work of interpretation of the spectators who venture to see the film. In the following paragraphs we will propose two clinical hypotheses regarding the experimenting doctor and his creature. As for the tragic value of the film, an interview with Almodóvar in the Festival of Cannes seems to second our conjecture: “Why do spectators laugh?” “Well, they shouldn’t …” possibly the best Almodovarian joke, and as such, should be taken seriously. Cain and Abel Let us see an example. One of the scenes most berated by the critics is the one in which Zeca, dressed as a tiger, bursts into the house of plastic surgeon Robert Legardt. This scene has been graded as “perfectly dispensable”, when in fact it is essential in order to organize both the logical and the narrative time sequence of the tragedy which provides the backbone of the film. The scene is there in order to reconstruct and culminate a story that goes back several decades -a tragic and disquieting story which casts unexpected light on present acts. It could be told like this: Marilia, who in those days worked as a maid for the Legardt family, becomes pregnant and gives birth to a baby boy who is taken in as their own by the family and christened Robert Legardt. Nothing much is said about the father of the child, but enough to know that the baby was the result of an amorous encounter with Mr. Legardt. Thus the young Robert grows up in ignorance of his origins, but raised by his biological mother, the domestic employee. The condition of not being recognized as the son will carry drastic consequences. A few years later, Marilia is again pregnant, the result of a fleeting relationship with a servant. After nine months her second son, Zeca, is born but this time she recognizes him as her own. She raises him in the city of Bahía, as by this time she has left the Legardt household and settled in Brazil. Zeca and Robert are therefore brothers born of the same womb, but they do not know this. This concealment has an ominous effect on Zeca who, as an adult, envies Robert’s fortune and his beautiful wife. This first section of the story, that explains the hostile nucleus between Zeca and Robert, reminds us, as mentioned in the Old Testament, that the relationship between brothers is never indifferent, it is never innocent. When the relationship cannot be of love, it ends by being one of hatred. Hence the biblical precept which ordains: thou shall honor thy father and thy mother, thou shalt not hate thy brother, in reference to the ill-fated destiny of Cain and Abel. We will return to this point later. The consequences of this ominous concealment that weighs upon the brothers are made manifest when Zeca seduces and conquers Robert’s wife and goes go away with her. The adventure ends in a car accident from which Zeca escapes practically unscathed, while Robert’s wife agonizes, her whole body enveloped in flames. Robert rescues her from certain death and tries to patiently reconstruct the tissues of her skin. He remains at her bedside for hours, in a dark room to prevent the sunlight from affecting the healing process. Nevertheless, the damage has been enormous and the scars are deep and impossible to hide. At one point the patient hears her daughter Norma singing in the garden, she opens the window and as she does so, she sees her own reflection in the glass. She screams in horror and throws herself out of the window, dying before the very eyes of her young daughter. The psychiatric problems that Norma will carry with her during adulthood appear as a sequel of this story, a story that will finally lead to suicide, following in her mother’s footsteps. With both his wife and daughter dead, Robert Legardt embarks on a reckless task of kidnapping and changing his victim’s identity by means of vaginoplasty, breast hypoplasty and xenotransplantations. The result of this experiment will be Vera, an androgynous creature who is kept captive and who Zeca will see through the monitors, when he goes to visit his mother, dressed as a tiger. We are now in the present of the narrative and we - the spectators - realize that Dr. Legardt has made Vera (meaning true in Italian) in the image and likeness of his dead wife. Zeca, who ignores the vicissitudes of the plastic experiment, once again envies his brother and ravages his new creature. Marilia, who by this time decidedly appears as a mother who propitiates crime and incest, is condemned to see with her own eyes the outcome of the tragedy she has engendered. Returning to Cain and Abel, let us recall that in the biblical tradition both are the product of the forbidden fruit that their parents, Adam and Eve, had indulged in, in disobeyance of Jehova’s law. Abel’s death in the hands of Cain, who was envious of his father’s preference for the latter, is the consequence of that transgression. But it must be read in the strict sense as a reciprocal, reversible movement that can affect both brothers interchangeably, since both are the fruit of the original ravage. In the alternative proposed by Almodóvar, Robert initially appears as the Abel of our story, the object of Zeca’s repeated envy; but on the reverse side of the plot, it is Robert who becomes Cain when he executes his brother for raping and deflowering his creature. In the manifest story, murder is shown as a defensive action against insult, but an analytical view reveals Robert to be envious of Zeca, whose sexual potency has no limits and contrasts with Robert’s (im)potence who, despite dildo “training”, cannot penetrate Vera. An interesting clinical hypothesis is opened with regard to Robert’s responsibility in the murder of his brother, a variation which, with Almodovar’s final twist, will return to fleetingly question him with the “I lied to you” in the lubricant cream scene. [7] Laius Whether it is in the Sophoclean version of Eteocles and Polynice, or the Bible of Cain and Abel, it is interesting to point out that the outcome is the product of the tragic structure which commands generations – Laius, Oedipus, Eteocles and Polynice. That tragic structure which returns in the ravaging of the third generation, was present in the morbid nucleus of the first – Oedipus says so in a speech, when he realizes that he had been living a pleasant life in Corinth: O Polybus! O Corinth! And thou, long time believed my father’s palace, Oh! what a foul disgrace to human nature Didst thou receive beneath a prince’s form! Impious myself, and from an impious race. It is interesting to note that the spectators of Almodóvar’s film sense the incestuous nucleus which inspires Dr. Legardt’s behavior, when they conjecture, for example, that maybe he sexually abused his daughter Norma. It is not a matter of confirming or denying this intuition, but of organizing the value of truth on which it is sustained - because it is evident that Legardt falls in love with a creature which nests in the body of he whom his daughter set eyes on for her uncontrolled lust. Let us go over the scene again. Legardt and his daughter Norma go to a party. We will later learn that she was under psychiatric treatment and this was her first outing, granted by her doctor and under the strict tutelage of her father. At one point Robert loses sight of his daughter. Almodóvar sets this scene in the middle of a moving song sung by Concha Buika – the lyrics of the song explain the father’s distraction, and to a certain degree the distraction of the audience in the cinema hall. When we recover from the spell, we see Legardt leaving the house in search of his daughter - the gardens have been turned into a sexual orgy –evident projection of his own lust. In the midst of it all, his daughter lies in a trance after a sexual encounter with a stranger, who escapes on a motorbike. And then the surprise: when he tries to bring her round, Norma mistakes him for her rapist and once again decompensates. In the following frame, back in the psychiatric clinic, the girl hides in a closet when her father enters the room to visit her. What does this scene say to us? Did Dr. Legardt abuse his daughter Norma? The question, we insist, has no answer, it is of no consequence to the cinematographic story, but has absolute sense in the symbolic plane, as Legardt’s behavior after Norma’s suicide puts us back on the track of his desire. He seeks the boy who had escaped that night, finds him, kidnaps him and holds him captive in the cellar of his mansion. And when the spectators imagine an exemplary punishment, an execution or long term captivity in the style of The Secret of her Eyes, Almodóvar proposes a spectacular turn of events. Legardt begins the metamorphosis operation and expects to make this boy the object of his never mentioned pedophilia. Vicente becomes the metonymy of his daughter and at the same time the failed resurrection of his wife. In Pier Paolo Pasolini’s version of Oedipus Rex, Laius appears as his son’s executioner, but also as the person who, on zealously watching over him, desires him. The baleful way he looks at the child, showing his hate but also his secret attraction, is a skillful way to meet Pasolini’s aesthetical and conceptual proposal that recovers what is essential to the pedophile nucleus. And Legardt, who is a version of the myth, is assimilated to the generation of brothers that exterminate themselves, embodies at the other extreme the origin of all evil, the father who desires childlike bodies and shallow cavities. You put it on (póntelo tú): responsibility for the skin we have to live in Finally, there is a film within the film – a frame story that the spectator can opt whether to see or not, as he wishes. We shall advance this thread by making a brief detour through another film; a film that also takes up the theme of responsibility with regard to plastic surgery, in this case restorative surgery. Open Your Eyes (Abre los ojos), by Alejandro Amenábar, or its better known version Vanilla Sky, with Tom Cruise in the leading role. The story can be summarized like this: Cesar, a young, pretty-face millionaire and seducer, holds a birthday party at his house. Nuria, a girl with whom he is having a passing affair, turns up to congratulate him and give him a present, with the hope of staying with him that evening. But Cesar rejects her and openly seduces Sofia, who arrives with Pelayo, his best friend. Pelayo notices the maneuver and knowing he stands no chance against Cesar, gets drunk and leaves the party. It is beginning to dawn and Nuria, who had been waiting for him, offers him a ride in her car so that they can be together in her apartment. He hesitates but finally he reluctantly accepts. He doesn’t realize that Nuria is drunk and probably high, and that above all else she wants revenge for the way he had mistreated her earlier. She drives recklessly and when she gets to a curve she puts her foot on the accelerator to make it go off the cliff. She dies in the accident but Cesar survives, but with severe wounds on his face. He undergoes different operations but the doctors only manage a poor reconstruction of his features, disfigured for ever due to the deep scarring. Horrified by the monster he has become, he rants against the doctors and demands another plastic surgery and refuses the face mask he is offered. [8] How does one handle a situation such as this from the medical-psychological point of view? One alternative is the one the professionals in the plot take when they try to console him with phrases such as “at least you are alive…” “it is a miracle that you only have injuries on your face”, etc. But these willful formulas do not comfort the patient, who in a fit of rage starts to show his hatred and resentment indiscriminately. In the end, the plot of the film reaches a fantastic solution, one in which the doctors end up offering an alternative by means of cryo-preservation combined with artifice and virtual reality workmanship. The ethical perspective that we wish to advance will here take a different path. An analytical look into the case will, first of all, try to understand the singular meaning of that wound for the patient. The clues to think about the case will most probably have to be taken from that fantasized, virtual world, which the character has designed to escape from anguish. But in order to take advantage of it, we should bracket the fantastic elements of the story and (re)read it as a delirium, a hallucination, a dream that becomes an eternal nightmare. In other words, like a setting in which the patient can become involved in his symptom. This view of the problem places the “bios” of the situation in parenthesis, reference to life as it appears trimmed by science, to establish the coordinates of the case in strictly ethical terms. With this change of focus, the guilt that torments Cesar, acquires a new dimension, providing us with a truth about the subject and his involvement in the accident. The true monster is not the one that showed up with the scars but one that lay in wait when his face was unscathed. He is the bad friend that has no misgivings about humiliating Pelayo by openly seducing the young girl who was with him; he is the irresponsible lover that hands out promises without measuring the consequences of his actions. And finally, he is the rogue who degrades the woman who loves him, thus precipitating the act that disfigures his own face. Only if and when Cesar (or David in the Vanilla Sky version) is able to bring himself face to face with that jouissance, will he be able to do something about his ‘mask’. This roundabout through Vanilla Sky makes us thinks of a thread on responsibility for the body we were lucky, or unlucky, to have been born with. Cosmetic surgery entails some points of no return and, although the risk is calculated, it does provide surprises. The character in Almodovar’s film and just as the character played by Tom Cruise in Vanilla Sky, will have to confront an unexpected mirror – and will probably deny his fate. But once more, the key to inhabit that new skin lies in being able to meet his desire in the midst of surgical loss. We close this article with one last enigma, inviting the spectator to follow the path of a piece of clothing that opens, with the last scene in the film, the conjecture, the promise of a new and unexpected film. It is about a possible way out of the tragedy by means of a meeting – of the decision of an encounter - imagined between two out of the ordinary lovers: a heterosexual man and a lesbian. The condition will naturally be the willingness to respond, body and soul, for that delicate boundary of skin that now inhabits and enables us.

Can an apprentice to Don Juan, an indiscriminate seducer, do something with the consequences of his lack of control? Where does he put the pills with which he drugs himself when these return in the ominous medication to which he is made object? And the most upsetting question of all: Can the subject find his jouissance while simultaneously falling in love with the blind spot he said he denied?

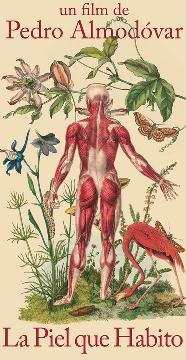

NOTAS

[1] Paper presented at the “Cinema and Subjectivity: Movements and Movies in Bioethics” Symposium, which took place November 24, 2011, in Buenos Aires within the framework of the III International Congress on Investigations and Professional Practices in Psychology, attended by the author and María Cristina Biazus (UFRGS). The papert originates from a research project, Movements and Movies in Bioethics, between the University of Oslo and the University of Buenos Aires, and coordinated by Jan Helge Solbakk and Juan Jorge Michel Fariña.

[2] The Concert ( Radu Mihaileanu, 2009) tells the story of a Tchaikovsky concerto for violin and orchestra, performed by the Bolshoi Orchestra, which in the fiction of the film, had not played together for thirty years. The musicians arrive on the evening of their debut at the Chatelet de Paris without having rehearsed – the beginning of the concert is disappointing. The orchestra sounds out of tune to the point where both audience and musicians feel uncomfortable. But everything changes when a violin makes its entry. Singularly inspired that evening, its timely entry saves the rendition and turns it into a masterly, unforgettable performance.

[3] See Michel Fariña, Bibliographic Dossier on Mental Health and Human Rights, UBA editions, 1992, pp10-11. On the cover of Vesalio’s book, the doctor is shown operating in front of a large auditorium full of spectators and at the foot of the image the barbers are depicted crying and the monkeys fleeing gleefully. The first because they are losing their jobs – they were the ones who did the dissections while the doctors read Galen out loud. The second, because they are finally escaping from the tragic destiny of the operating table.

[4] See Gutierrez, C. “The decision in face of death in Blade Runner.” In (Bio)ética y Cine: Tragedia griega y acontecimiento del cuerpo, Michel Fariña y Solbakk (Ed.). Buenos Aires, Letra Viva, 2012.

[5] According to J. Hardy (Hardy, 1932, p16), there is no fragment more famous in Greek literature than this one of Aristotle’s, taken from Poetics, where in few words catharsis is dramatically characterized as interrelated with the painful emotions of pity (eleos) and fear or terror (phobos). The reference is taken from Solbakk JH, Catharsis and Moral Therapy II: An Aristotelian account, Journal of Medicine Healthcare and Philosophy, 2006;9(2):141-153.

[6] For the Greeks, the punishment of Gods are inexorably imposed, and this is one of the teachings of tragedy: while human laws have punishments that require worldly intervention, violation of the laws of the Gods means inevitable punishment by the gods themselves. In the case of Laius, the curse is fulfilled and Oedipus is the instrument of that punishment. That is why the curse is transmitted to three generations, till there is nobody left to continue transmitting it.

[7] Finally, on the reverse of his phantom, impotency with regard to his wife – who seeks Zeca to satiate her sexual appetite - is being played out. The late, futile lust for Vera, then only after, and because, he had seen – propitiated- the brutal rape his blood brother inflicted on her.

[8] For an analysis of this film, from the clinical perspective, see article by Julieta Loza “Units of Help: professional responsibility in face of subjectivities razed by disfigured faces”. In minutes of I International Congress on Ethics and Movies, extracted 11/20/11 http://www.eticaycine.org/Vanilla-Sky